Deforestation and International Timber Trade Agreement(ITTA)

Although deforestation and forest degradation were recognized as severe environmental problems, there is no legally binding instrument tackling deforestation directly. Deforestation has been included as a sub-issue of many environmental institutions. Among such instruments relevant to forests is the International Tropical Timber Agreement(ITTA), which entered into force in 2011, superseding the original agreement signed in 1994. As assumed in its name, The ITTA deals with commercial and industrial tropical timber products. Under the ITTA, International Tropical Timber Organization(ITTO) was established.

Before we delve into the ITTA, I would like to show you how forest degradation and deforestation have been defined in a global society. Here are some examples of the definition of deforestation and forest degradation :

Deforestation is the direct human-induced conversion of forested land to non-forested land.

Marrakech Accords(7th Conference of the Parties, COP7), UNFCCC

Deforestation is the conversion of forest to another land use or the long-term reduction of the tree canopy cover below the minimum 10 percent threshold.

FAO, 2001

Forest degradation is the long-term reduction of the overall potential supply of benefits from the forest, which includes carbon, wood, biodiversity and other goods and services.

FAO, 2003

A degraded forest is a secondary forest that has lost, through human activities, the structure, function, species composition or productivity normally associated with a natural forest type expected on that site. Hence, a degraded forest delivers a reduced supply of goods and services from the given site and maintains only limited biological diversity. Biological diversity of degraded forests include many non-tree components, which may dominate in the under-canopy vegetation

UNEP/CBD 2001

Forest degradation: A direct human-induced long-term loss (persisting for X years or more) of at least Y % of forest carbon stocks (and forest values) since time T and not qualifying as deforestation or an elected activity under Article 3.4 of the Kyoto Protocol.

IPCC, 2003 b1

Forest degradation is a direct human-induced loss of forest values (particularly carbon), likely to be characterized by a reduction of tree crown cover. Routine management from which crown cover will recover within the normal cycle of forest management operations is not included.

ITTO, 2005

As you can see, the definition of deforestation and forest degradation varies depending on the perspective of instruments. However, most definitions touch on or agree on in some way human-induced, long-term, negative changes in the forests' structure, function and capacity for the provision of goods and services. The reason why I chose the ITTA to discuss the challenge is that it directly deals with one of the causes of deforestation, forestry. It contributes to about 26% of the whole forest loss in the world. (This sort of figure should be carefully put as definitions of forests quite vary and also the collected data might be distorted. Still, this number gives us an idea of how significantly humans negatively affect our nature.)

As commodity-driven deforestation accounts for the larges part, it is crucial to solving the dilemma between economic gain and ecological loss to address this environmental problem. What makes it even more challenging is that tropical forests are mostly found in developing countries. To such fewer income countries, economic benefits in the short term seem more attractive than the ecological benefits that conserving forests bring. Still, protecting tropical forests has become an important task to our global society not only for biodiversity but also for the mitigation of climate change. Keeping in mind the importance of tropical forests, the rest of this blog post analyses more in detail how the ITTO addresses/has addressed such an economic driver of deforestation and what challenges the ITTO has faced in solving deforestation.

Who is involved in the ITTO?

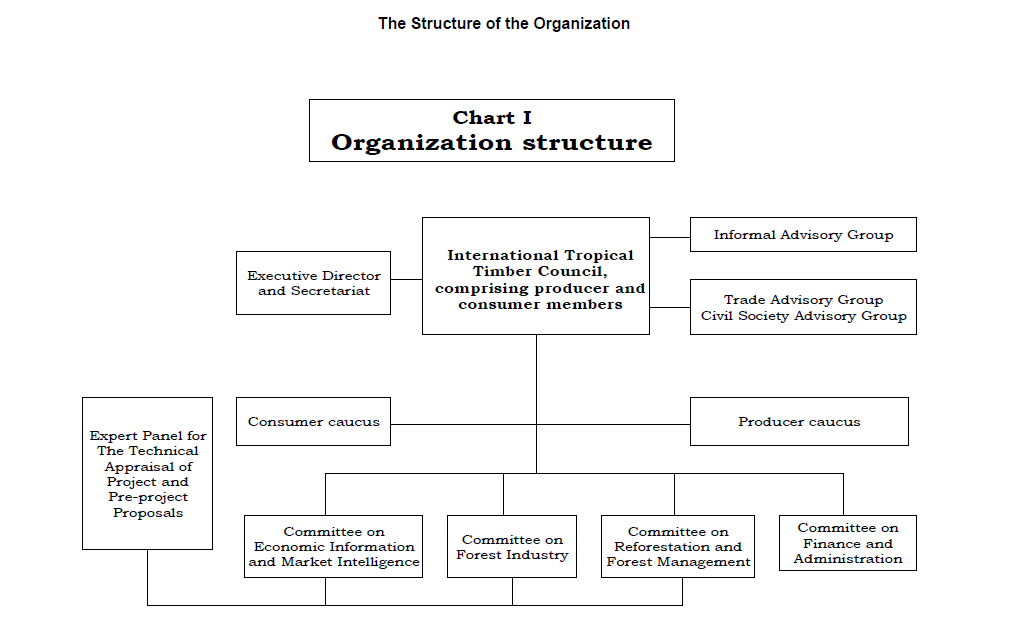

According to O’Neill(2017), nation-states, international organisations(IOs), the global environmental movement, the corporate sector, and expert groups are the main actors in the environmental regime. Within the ITTO, the most powerful actors would be the member states because the ITTA restricts its membership to governments or intergovernmental organizations such as the EU. As shown in the above network map, member states are categorized into two groups, producing countries and consuming countries. Currently, there are 36 (net) producing members and 38 (net) consuming members. This remaining division until now shows that the ITTO has kept its position as a trade commodities organization rather than environmental problems. In this network map, I made clear which member states heavily financed the ITTO during the recent two years which are China, the European Union, Germany, Korea, Japan and the USA. The thickness of connection to ITTO is proportional to the amount of their annual funding.

Still, the ITTO has several partners, mostly IOs and environmental non-governmental organizations(ENGOs). The role of the UNCTAD was especially important in building this international tropical timber regime. The UNCTAD/FAO(Food and Agriculture Organization) working party on forests and timber products proposed to build an international bureau for tropical timber, which now became the ITTO. ENGOs like the World Wildlife Fund(WWF) and UK Friends of the Earth (FoE-UK) and IOs like the International Union for Conservation of Nature(IUCN) also contributed to drawing an agreement by all the parties through their effective lobbying during the preparation stage of the ITTA.

Looking more closely at the current partnership, the ITTO has broadened their partnerships with other organizations. Ranging from UN organizations to private sectors, the ITTO has diverse partners to support and promote sustainable forest management (SFM) projects. Two collaboration projects are going on at present, respectively with the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora(CITES) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Some organizations such as IUCN and World Bank even financially support the ITTO. However, such participation of international economic organization like the World Bank or WTO does not always have positive aspects. As O’Neill(2017) explains, some think their preference of liberalized trade policies can lead to detriments of nature, while others think they result in economic growth which allows the governments to protect nature. In the case of ITTO, however, their engagement rather reveals the preservationist approaches of the ITTO in addressing deforestations. You might already notice that well-known ENGOs such as Greenpeace or WWF are missing in the network. Interestingly, the WWF is no longer in a partnership with the ITTA, although they put huge efforts into the ITTO in its beginning. Gale (1996) attributes this absence of conservationists or environmentalist organizations within the ITTO to its prioritization of timber trade over conservation of forests.

States, the main actors of the ITTO

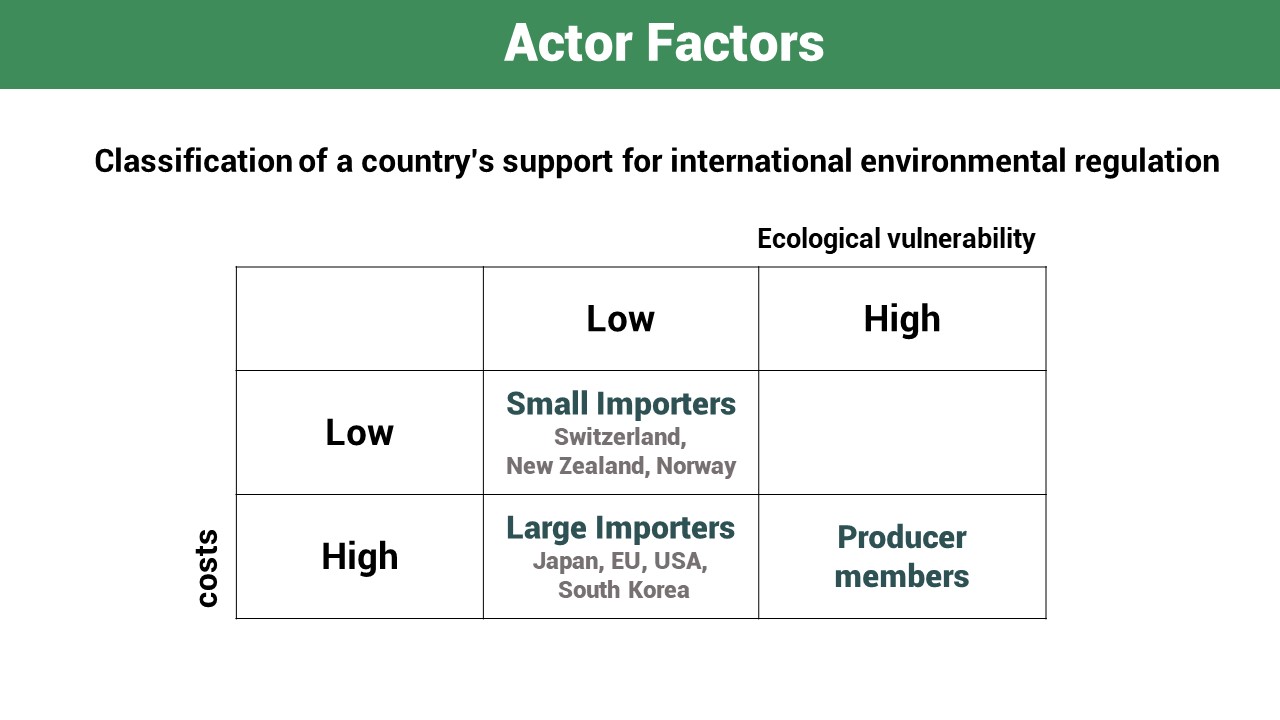

Such tendency of ITTO privileging timber trade over forest protection can be explained by the interests of its main actors, national states. Using the actor framework of Sprinz & Vaahtoranta(1994), member states can be divided into four groups as described in the following table. Among four groups, “pushers” are the most active members in implementing environmental regulations. Both “Bystanders” and “Intermediates” are less likely to be motivated because the former feels fewer needs and the latter feels too costly. The least interested and often uncooperative group is “draggers”.

First, in terms of ecological vulnerability, producing countries tend to be more vulnerable than consuming countries. Of course, deforestation directly or indirectly affects all the living ones on our planet. Still, considering the short-term and direct negative effects of deforestation, producing countries are more in danger due to the short distance from the forests. Regarding the costs to abide by environmental regulations, the bigger the amount of trade the states are engaged in, the higher they feel the costs. Obviously, regulations on logging tress will hit harshly on the economies of countries that export or import a great deal of timbers.

Applying this framework to the case of the ITTO, small (net) importers such as New Zealand and Switzerland fall into “Bystanders” and large (net) importers such as the USA, Japan, the EU and South Korea fall in “Draggers”. On the other hand, most (net) producing countries are “Intermediates” because environmental regulations on deforestation affect quite significantly the economy of such countries. While the majority of consuming countries is developed countries, all producing countries of the ITTO are developing countries categorized by the World Bank. Therefore, such a loss from the timber exportation has a great economic impact in producing countries than in consuming countries. Considering the negative long-term effects induced by deforestation, some producing countries should be also put in the position of “Pushers” as well. Indeed, Brazil and Indonesia were very keen on banning exports of logs from the tropical forests in the 1970s and 1980s. However, due to pressures from IOs like the International Monetary Fund(IMF), they switched their position to be exports-oriented with tropical timbers and ended up being “Intermediates”.

This actor factor analysis well explains one of the biggest challenges of deforestation, the absence of great interests of governments in implementing regulations on deforestation. During the 1st negotiation session for the ITTA 2006, the European Union, South Korea and China clearly specified that the ITTA should remain as a commodity agreement. Only New Zealand mentioned that ITTO should take care of some new environmental problems. Besides, there was no single country that insisted on strong measures on forest conservation. Rather, some producing countries interestingly took the position of “draggers”. Suriname and India, for example, showed preference on putting emphasis strictly on timber trade as an objective of the ITTA during the 4th negotiation, interestingly, some producing countries were rather in the position of “draggers”. Due to this lack of countries strongly favouring forests conservation, the ITTA remained the ‘business-as-usual stance on the deforestation problems, focusing on the facilitation of tropical timber trade with SFM.

Do design features of the ITTO help to solve deforestation?

Moving on from the actor analysis, this section will show the design features of the ITTO and how they are linked to the problem structure and also the participation of members. According to Koremenos et al (2001), design features of the regime can be explained as a response to the problem structures and settings. Design features are also closely linked to the participation of actors in international cooperation as Bernauer et al (2013) examined. Using the design characteristics studied in the research of Koresmenos et al (2001) and Bernauer et al (2013), I coded the design features of the ITTO as below:

| Design Features | Coding |

| Membership | Inclusive by design/ Restricted to government, the European Community or any intergovernmental organization, still open to cooperating with other organizations/ potential consumer or producer numbers listed in the annexe |

| Scope | Mainly the issue with the trade of tropical timber and tropical products from sustainably managed sources and reducing deforestation/forest degradation |

| Specificity of obligations |

Achieving exports of tropical timber and timber products from sustainably managed sources (ITTO Objective 2000) |

| Centralization | The highest authority: the International Tropical Timber Council(ITTC), which develops forest-related policies and approve and finance field-level projects. Each member shall be represented in the Council by one representative. |

| Monitoring | No monitoring but voluntary knowledge & information sharing (statistics and information on timber, its trade and activities aimed at achieving sustainable management of timber producing forests) |

| Control | Each group(Producers and Consumers) hold 50% of the votes but member states whose share in the trade higher hold more votes. |

| Dispute settlement mechanisms | Complaints and disputes taken by consensus in the Council |

| Enforcement mechanisms |

No enforcement mechanism |

| Flexibility | Remain in force for 10 years with the possible extension twice. The Council can terminate at any time with the special vote. Members can amend or withdraw the agreement with the special vote. |

| Assistance | The Executive Director shall provide assistance in the development of proposals for pre-projects. Funding is allocated to the countries in need. |

To see how those design features match the problem settings, it is important to understand the problem structures first:

Involved Actors: Both 36 producing and 38 consuming countries are victims and perpetrators (symmetric). Producers log the trees but consumers buy these products. However, geographically and economically, producing countries are more likely to suffer more from deforestation in general (asymmetric)

Distribution Problem: The states would like to cooperate but they have conflicting points of views (similar to the game theory "Battles of Sexes"). As seen during the negotiation process, the producing countries request more financial and technological assistance than the consuming countries think it is sufficient.

Enforcement Problem: Since both economic profits and environmental problems are not negligible, actors feel mixed incentives on environmental measures.

Uncertainty: The preferences of each party are quite transparent, but non-compliance of other parties is not easy to attribute. The risks of deforestation are recognized. Still, indirect negative effects from deforestation are not tangible and it is not feasible to check every single production process of timbers in the forests due to geographical constraints.

Considering that the deforestation in tropical forests shows quite a moderate level of each variable of problem structure, this quite loose but centralized structure of the ITTO can be well understood.

One of the most interesting conjectures within this analysis would be the relations between actors and control. As mentioned in the table, both consumer and producer countries hold equal amounts of votes so the control over the other group is restricted. However, the parties with a bigger share in the trade have more power in voting. Referring to the network map again, some consuming countries have been financially more contributing to the ITTO than other members. Such financial assistance has played an important role in implementing diverse projects of the ITTO since many other producing countries consistently asked for more support. Also, implementing SFM within the ITTO affects more the countries engaging in a bigger volume of trade. Therefore, such asymmetricity among members has allowed the ITTO to have such an asymmetric and complex voting procedure. However, such influence of large importers and exporters in the ITTO eventually prevented from protecting the forests, leveraging the regime to a continuation of timber exploitation. As Nagtzaam (2016) explains in his article, such homogeneity between large importers and exporters made the promotion of conservationist norms within the ITTO a difficult task.

Then, how these design characteristics affect the participation rate of the ITTO? According to Bernauer et al (2013), the specificity of obligations, monitoring and enforcement mechanisms tend to negatively affect participation, while dispute settlement mechanisms, assistance and organizational structure lead to promote participation in the regime. In the case of the ITTO, there are no significant features that would hamper the efforts of member states to join the regime. Although some countries such as Angola, Bolivia, Canada and Egypt have left or do not join the ITTO, the ITTO shows high popularity covering 80% of the tropical forests and 90% of the total tropical timber trade in the world. Yet, this success of the large participation raises the question of the depth of efforts that the ITTO has made to promote SFM. Considering the absence of specific targets, monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, it is not easy for the ITTO to avoid that criticism that they were “shallow” in promoting sustainability in the tropical forests.

Conclusion

Throughout analyzing the actors and the design features of the ITTO, I could see several deficiencies of the ITTO in addressing the problem of deforestation. First of all, there are not many actors within the regime who are strongly in favour of protecting the forests. Even conservationist ENGOs have already left the ITTO. Second, both actors and deforestation problems per se are highly linked to economic issues. This created a sort of vicious cycle, making the design feature of the ITTO very weak in implementing the projects independently from the member states. This lack of enforcement mechanism and specificity in its target enabled some powerful states to manipulate the regime. Lastly, the ITTO seems not free from the participation-depth dilemma. Especially Canada withdrew the ITTA after the discussion on the financial mandates(although the exact reason is not clear). Yet, the ITTO would need to arrange more stringent measurements with specific mandates of each member to accelerate the promotion of SFM and achieve its goal, also hopefully to prioritize environmental concerns over economic ones.